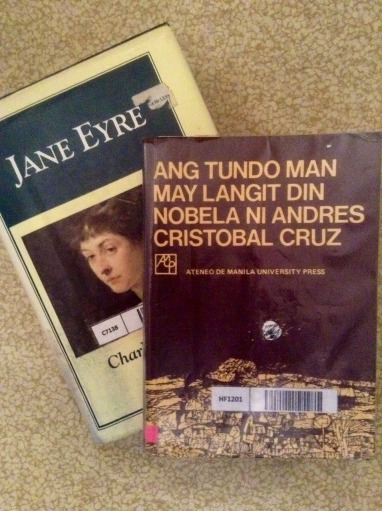

Among the books that I borrowed from College of the Immaculate Conception in Cabanatuan City were the Filipino social realist novel Ang Tundo Man May Langit Din (Even Tundo Has a Piece of Sky) by Andres Cristobal Cruz and the British Gothic novel Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë. I once heard a CIC professor complaining about the meager resources of the school’s libraries- I was surprised because I’ve often found on their shelves gems to read such as these.

I read Cruz’s novel- the chapters were first published in Liwayway magazine from 1959 to 1960- while reading Tristram Shandy so I could immerse myself in my own language and in images with which I was familiar. The protagonist of Tundo, Victor del Mundo- a working student-turned-teacher- could have been one of my classmates in college: he reminded me in particular of my classmate Florin Hilbay who also grew up in Tundo, topped the bar exams, and is now the Solicitor-General. In the first chapter, Victor walks from the printing press where he works to Quiapo, Raon, and Quezon Boulevard, places that I explored much later in the 1990s and 2000s, but nonetheless still fit Cruz’s descriptions. I remember my Waze app telling me last year I was passing through Tundo- Manila’s most densely populated district- but I don’t remember setting foot on its streets (I associated it, perhaps incorrectly, with gang wars). I was therefore fascinated by the novel’s setting- Victor’s gritty neighborhood in the 1950s- and the rough, yet very human, characters who appear therein.

I finished reading Tundo on February 27 and Tristram Shandy on March 1. A couple of days later, I began reading Jane Eyre, the second selection of Slate Academy. I’m now halfway through Charlotte Brontë’s engrossing tale of the thoughts and feelings of an abused orphan who grew up to find her identity and her place in the sun in northern England in the early 19th century. Just like in Tundo, the love story in Jane Eyre involves lovers- Jane and Rochester- from two different social classes. Jane is a governess- the tutor of Rochester’s foster child- and she calls him her “master.” In Tundo, however, the class roles are the other way around: the male protagonist Victor is pursued by his wealthy classmate Alma.

I’m struck by how similar courtship is represented in these two novels: as an exquisite dance of pain and pleasure.

Throughout their courtship, Victor loves to tease Alma until she becomes angry and pinches his arm.

In the middle of Jane Eyre, Rochester makes Jane cry by making her think that he is about to marry the rich Miss Ingram- by making Jane jealous, he is able to make her confess her affection for him.

“I tell you I must go!” I [Jane] retorted, roused to something like passion. “Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you? Do you think I am an automaton?-a machine without feelings? and can bear to have my morsel of bread snatched from my lips, and my drop of living water dashed from my cup? Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong!-I have as much soul as you,-and full as much heart! And if God had gifted me with some beauty, and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you. I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, or even of mortal flesh:-it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal,-as we are!”

In both novels, the protagonists face rigid class systems that prevent them from immediately realizing their dreams. Tundo ends on a happy or at least hopeful note and- romantic that I am- I hope Jane Eyre does too.